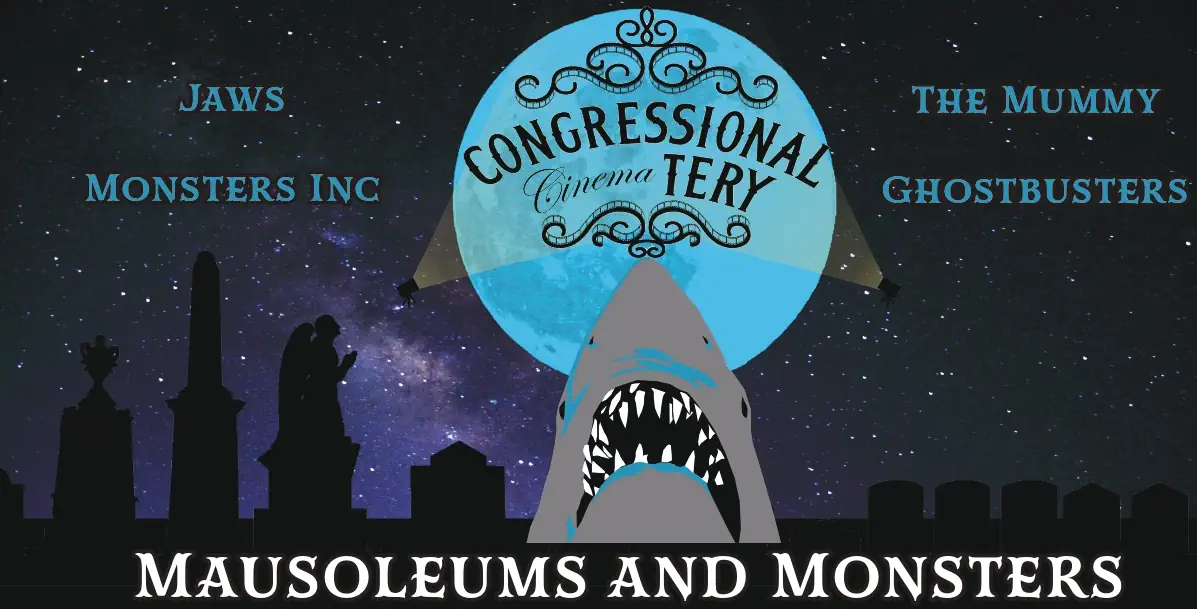

This is part 2 of a two part series about life and death in DC before the advent of scientific body donation. To see part 1 of this harrowing tale of late-night grave-robbing and underhanded medical practices, please see part one here.

Body snatching did not end in Washington D.C. when Dr. George Christian left town. Infact, the practice continued well into the 1880s. On the night of December 20th, 1889, the bodies of two women, one Black and one White, were found inside a carriage. It had been parked on the street near the District’s jail at 19th and Bay Street for several days, presumably waiting for cadavers to be procured. It was assumed that both bodies came from the nearby potter’s field (Independence & 19th) where it was common for bodies to be stolen and sold to the city’s medical colleges. In fact, when a man called at the morgue the next day seeking permission to view the white woman’s body because his sister had recently been buried at Congressional, the station clerk assured him the bodies came from the Potter’s Field, where the unidentified, indigent and/or unclaimed were buried.

Hains, Peter C, and United States Army. Corps Of Engineers. Map of Anacostia River in the District of Columbia and Maryland. [Washington, D.C.?: Corps of Engineers, 1891] Map.

https://www.loc.gov/item/88690696/

However, one policeman thought the white woman’s body looked “too refined” to be from a pauper’s grave. Though the rest of her clothes had been removed, an undergarment said, “B. Cheek ” inside. When the officer searched health records, he found that Mrs. Alvina Cheek had died on December 14th of tuberculosis and had been buried at Congressional Cemetery on the 17th. (Range: 1, Site: 257a)

Alvina “Venie” Cheek, 24, had been buried along with her infant, only a few days old, “on a knoll overlooking the Anacostia river and not far from a gate which opens into the rear end of the work house grounds.” The Superintendent, Mr. Cross, said the graves were undisturbed but Alvina’s husband, Thomas, confirmed the identification. After Venie’s body was taken, the grave had been refilled and Thomas’s flowers placed where they had been on top. After Venie’s remains were recovered, they were placed in Congressional’s receiving vault for a few days (perhaps until her body would no longer be useful for dissection.)

Day by day we saw her fade

And slowly sink away,

Yet in our hearts we prayed

That she might longer stay.

I was weeping around her pillow

For I knew that she must die;

It was night within my bosom,

It was night within the sky.

I have given love’s last token,

I have parted back her hair

From off the marble forehead

And left the last kiss there.–By Her Husband

Mary Hawkins was identified as the Black woman whose body was found in the buggy with Venie Cheek. Unlike Cheek, Hawkins’ remains were in fact stolen from the Potter’s Field. These locations were popular targets for Resurrectionists because the pine coffins commonly used were easier to break open, the cemeteries often lacked guards and fencing, and mourners were less likely to visit and discover a grave disturbed.

“Reward Advertisement.” Evening Star, December 24, 1889

The trustees of Congressional Cemetery offered a reward for the apprehension of the person or persons responsible for the theft of Mrs. Cheek’s body and hired two additional watchmen. Initially police fingered Dr. Arthur Adams, who had come to the police station to inquire about the carriage that the two women were found in. However, Adams had several students and a janitor assert that he was at the National Medical College, where he taught anatomy, that night. Thomas Cheek, devastated and seeking the return of his wife’s jewelry, visited Dr. Adams several times hoping for information. Eventually Dr. Adams claimed that Dr. William Beall was actually the owner of the buggy.

In her thesis, Death is Never Over Life, Death and Grave Robbery in a Historic Cemetery, Rebecca Boggs Roberts suspected that Beall was employed by Dr. Adams. She argued that Beall was not on the membership lists of the Medical Association of the District of Columbia in the 1880’s. Dr. Adams’ past business with resurrectionists certainly supports Roberts’ idea that Beall was procuring bodies for Dr. Adams. In 1884, a reporter from the Critic interviewed notorious body snatcher Vigo Jensen Ross in his cell. He was anxious to see Dr. Adams who he furnished with cadavers because anatomy professors often assisted resurrectionists with their bail or testified in their defense.

History of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia. JAMA. 1948;137(12):1093–1094. doi:10.1001/jama.1948.02890460089033

Policeman Charles W. O’Neill, also a member of the board of trustees of Congressional Cemetery, issued a warrant against Dr. W. W. Beall on December 24th, 1889. Beall was charged with desecrating the graves of Mary Hawkins and Alvina Cheek. Police had also hoped to charge him with larceny for stealing Mrs. Cheek’s jewelry, but they weren’t able to make a case.

When police went to arrest Beall at his son’s grocery store, his son didn’t know where he was or when he’d be back. Police learned that he had left the city in a carriage, so they went to Beall’s brother’s farm in Montgomery County, Maryland the next day. When Beall saw detectives, he ran first in the direction of woods and then towards a barn. While police were unable to locate Beall on the farm, his brother served them cake and wine. He explained that his brother simply wanted to spend Christmas Day there before turning himself in, which he did on December 27th.

The Trial of Dr. W. W. Beall began January 4th, 1890. Inside the wagon with the bodies, police found an iron hook which they believed was used to remove the women from their graves. A blacksmith testified to having made a similar hook for Dr. Beall. Dr. Adams testified to recovering Beall’s horse and buggy for him but, denied that “he paid any money, directly or indirectly to the defendent.” The Undertaker, Mr. Cheek, and the workhouse ambulance driver also testified. The final witness called by the prosecution was “Brocky” White. He said he worked for Dr. Beall and previously assisted him with getting bodies from the potter’s field. Brocky said Beall made an average of three resurrecting trips per week.

Three witnesses provided Beall with an alibi. However, at least one of the witnesses was thought to be his accomplice. On the evening of January 8th, 1890, a crowd gathered by gas light to hear the trial end. In total, the judge imposed a fine of $400 (over $13,000 in today’s money) and imprisonment for six months as a sentence ($200 and 90 days for each case.)

In 1888, as a result of the Cheek case, a bill was proposed that would give medical schools in the District access to bodies from alms houses and hospitals. However, it did not pass. It wouldn’t be until the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act of 1968 that any adult would be permitted to become an organ donor or that ways to donate one’s body to medicate became prescribed. Body donation is vital for training the next generation of doctors and developing mental techniques. Society will always need to look at how we balance scientific study and advancement with cultural attitudes and respect for our dead. Thankfully today, it’s more common for people to choose to donate their bodies to science.

Where can you donate your body to science in the District?

The College of Medicine at Howard University

The School of Medicine at Georgetown University

*As of February 2023, George Washington University is no longer accepting body donations.

Instagram: @bonesandgravestones

Works Cited

“Alvina Cheek Obituary.” Evening Star, December 16, 1889.

“Couldn’t Catch Dr. Beall.” Evening Star, December 26th, 1889.

“Dr. Beall in Court Today.” Evening Star, December 27, 1889.

“Dr. Beall’s Sentence.” Evening Star, January 9, 1890.

“Jensen Will Fight Case.” The Critic, October 11, 1884.

“Reward Advertisement.” Evening Star, December 24, 1889.

Roberts, Rebbeca Boggs. “Death is Never Over Life: Death and Grave Robbery in a Historic Cemetery.” Thesis. Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, George Washington University, 2012.

“Spade and Iron Hook–The Beall Grave Robbing Case Takes Up Today.” Evening Star, January 4, 1890.

“The Body of Mrs. Cheek.” Evening Star, December 23, 1889.

“The Double Grave Robbery–Testimony Against Dr. W. W. Beall in the Police Court Saturday.” Evening Star, January 6, 1890.

President's Pick

May 17, 2022

stay up to date

When you sign up for our mailing list, you’ll receive closure notifications, event information, and general updates.