The staff here often refer to cemeteries as outdoor museums. Our “collection” on the grounds consists of over 14,000 headstones, each one in need of proper care and conservation, and each one has a written story to tell. Some stories are more detailed than others, but every headstone is a historical record that memorializes the interred individuals.

But what about the people who left their mark on Congressional Cemetery who are not memorialized in stone? The archives are full of people – both alive and dead – whose transient visits to the Cemetery are impossible to detect on the landscape. But, such is the power of place, and the importance of historical archives. It is more difficult to detect the unseen stories here because there are so many visible, tangible markers for past people and events. But by looking closely at the interment records, newspaper articles, and letters, it’s possible to peel back another layer of the past and discover a new dimension of Congressional Cemetery.

The Public Vault in happier times.

As any historic interpreter worth their salt will tell you, though, empty spaces can still speak volumes about the past. We use our Public Vault quite often here for tours, cocktail parties, and lectures. Although the musty interior lends a definitively creepy vibe to our events, it’s still difficult to envision the hundreds of human remains that utilized the vault as a hotel room before heading to their permanent destinations, often to a grave in HCC. As is oft-recited on our tours, three presidents spent time in our Public Vault: Zachary Taylor, John Quincy Adams, and William Henry Harrison – who actually spent more time in the Public Vault than in the office of the President (yes, that’s one of our very favorite nerdy jokes here). But someone we really feel we can stake a claim to? Dolley Madison, former First Lady and widow of President James Madison. She spent over two years in the Public Vault before heading to the vault across the way, the Causten Vault, for nearly six years. Looking through HCC records, staff also discovered that Dolley had another First Lady join her in the Causten Vault for a few months – Lousia Adams, wife of John Quincy Adams.

Dolley and Louisa: friends in death?

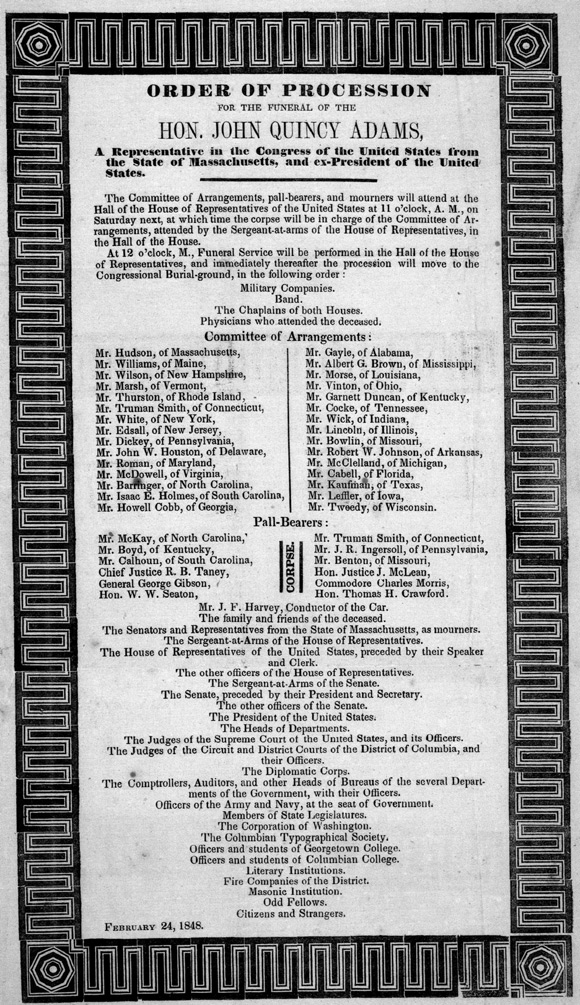

The Public Vault records boast an impressive roster of names that often seem lifted from a U.S. History textbook, and it makes sense that a certain degree of pomp and circumstance accompanied them on their journey to the receiving vault. Congressional Cemetery was the final destination for numerous grand funeral processions in antebellum Washington, DC. The cenotaphs that dot the landscape mark and memorialize only a fraction of the Congressmen, Presidents, and other influential individuals who were a part of the funeral processions that ended here. Abraham Lincoln was a part of many funeral processions when he was both a Representative and President. Most notably, Lincoln was noted as the “Chief Mourner” for the women who perished in the Washington Arsenal explosion in 1864. But the list of pallbearers for national funerals is also impressive: the likes of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun show up on the list. Moreover, a few of the participants in the funeral processions would end up later being buried in the Cemetery, including Joseph Gales, owner of the National Intelligencer, a publication which recorded the details of many of these funeral processions.

Funeral Order of Procession for John Quincy Adams.

So what, you might say? Important dead people stayed at the cemetery for a bit, and more important people accompanied them on their journey. It might seem to be a natural fit and progression for a national cemetery to host impressive historical figures such as Lincoln and Dolley during funerals and in preparation for burials. But every once in a while something pops up in the records about Congressional Cemetery that has nothing to do with death. One of the more salacious historical happenstances is the affair between Philip Barton Key and Teresa Sickles, which tragically ended with Teresa’s husband, Dan Sickles, murdering Key. Key, whose father penned “The Star Spangled Banner,” was a notorious womanizer, but was a widower when he managed to woo Teresa Sickles. They conducted their affair all over the city of Washington, including Teresa’s home. But most notably, for this article anyways, they also frequented burial grounds for their illicit liaisons, including the cemetery on the east side of the city – Congressional Cemetery. Court records detailed the testimony of Teresa Sickles’ coachmen, who noted that “they would walk down the grounds out of my sight, and be away an hour or an hour and a half.” Take from that what you will, of course.

The murder of Philip Barton Key – which did NOT happen at HCC.

These might all seem to be disparate and unrelated anecdotes, and perhaps they are. Congressional Cemetery’s history is overwhelming enough when you just take into account the thousands of interments here, much less any tangential history that happened to brush by during the Cemetery’s 210-year stretch. But there’s something to be said for attempting to understand and reconcile the history that is not inscribed on the monuments. This hallowed ground has been trodden by presidents and generals, scoundrels and statesmen, and these are only a few of the stories that pepper the landscape of our records and imaginations. The significance of Congressional Cemetery is much more than what is clearly visible. It has been touched by thousands of people, and will continue to be experienced and influenced for years to come. Within the course of a single year this Cemetery witnesses a multitude of events: daily dog walks, marriage proposals, runs, and of course, funerals. Through our records we get a glimpse of the past events that have shaped Congressional Cemetery, and they influence the way in which we view the present. We’re each a part of Congressional Cemetery’s story.

–Lauren Maloy, Program Director

Thank you for all of the wonderful stories you have uncovered over the years and thank you for sharing them with your readers.

From Colorado, thank you again for a fun read.

Glad you enjoyed it!

And thank you for taking the time to read them.

Love the Key story!!