Recently, the National Park Service awarded a $6,500 matching grant through the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program. The grant will provide funding for four interpretive granite and bronze footstone markers at the grave sites of William Boyd, John Dean, Hannibal Hamlin, and David Hall.

Historian Sandy Schmidt has completed countless hours of research into the connection between these individuals and the Underground Railroad, and has advocated for their inclusion in the Network to Freedom program. Thanks to her, Congressional Cemetery is included on the Network to Freedom. Sandy wrote the article below for inclusion in Congressional Cemetery’s Fall 2013 Newsletter, and you can learn more about her research on Washington, DC history at her website, http://bytesofhistory.org/.

Congressional Cemetery and the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom

By Sandra Schmidt

Congressional Cemetery was first accepted to the Underground Railroad (UGRR) Network to Freedom in March 2010. An amended application including 2 more individuals was approved this September. As a site on the National Register of Historic Places, Congressional qualifies as the burial site of four individuals associated with the UGRR – William Boyd, John Dean, David A. Hall and Hannibal Hamlin.

The Network to Freedom is a national network of sites, programs and facilities with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad. Its purpose is to educate the public and encourage documenting, preserving and interpreting UGRR history. The Network to Freedom was authorized by the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-203) and is managed by the National Park Service. The website (http://www.nps.gov/ugrr) and application process were officially launched in October 2000. Since then nearly 500 sites, programs and facilities throughout the U.S. have been accepted by the Network’s review board.

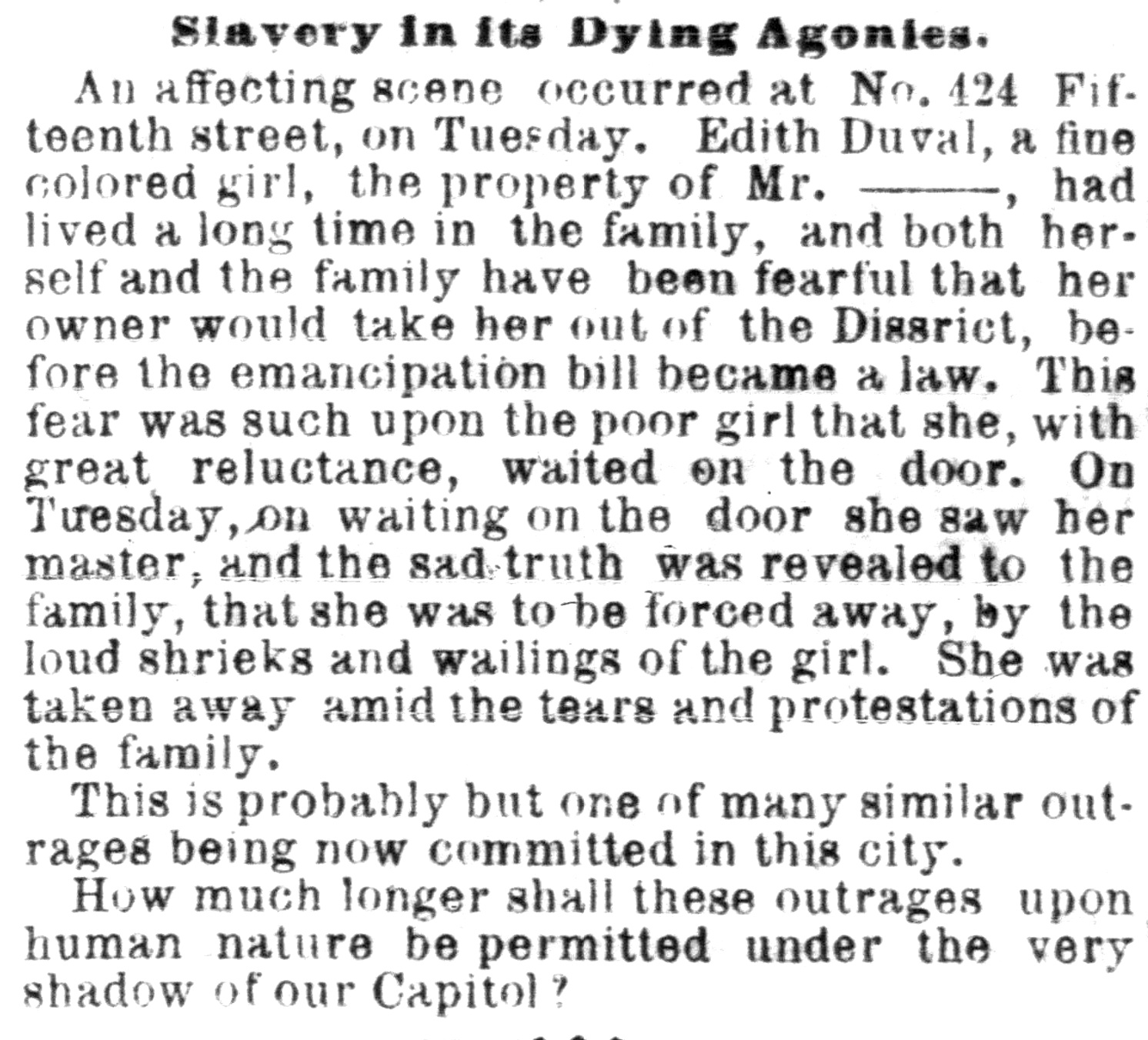

William Boyd (1820-1884, R5 S222) was a “conductor” on the UGRR. In November 1858, he was caught near the Pennsylvania border with two escaped slaves concealed in the back of his wagon. It is not known how many other slaves he helped to freedom, but at his trial, witnesses testified they had seen his wagon on other occasions. Boyd was sentenced to 14 years in the penitentiary for stealing slaves. He had served only 3 years when 54 members of Congress – all of the officers of the Penitentiary and other prominent citizens of the District – petitioned for his pardon. President Lincoln signed the pardon on October 3, 1861. Boyd’s efforts on behalf of the black community did not end there. During a riot in June 1865, when a crowd of rowdy soldiers began looting and beating the black residents in Southwest D.C., Boyd was hit in the head with a brick. A soldier was about to strike him with an axe when a group of black women intervened. He lost an eye and was so severely wounded doctors gave no hope for his recovery. He did recover, but never fully. He went on to serve on the Board of Common Council in 1869, and was a leading member of the Republican Party in Southwest Washington, where he argued for the rights of the black community.

Both David A. Hall and John Dean were attorneys who provided legal aid to freedom seekers and other participants in the UGRR. David Hall (1795-1870, R34 S63) arrived in the District in about 1820 to study and practice law. There are numerous examples of cases heard before the DC and MD courts in which Hall defended or negotiated on behalf of freedom-seekers. Among them are the petition he wrote which Rep. Joshua Giddings presented in Congress on behalf of a black Virginian who had been falsely imprisoned as a runaway slave and was about to be sold to pay his “lodging” expenses. In 1848 he was the first attorney to come to the aid of the officers of the Pearl and the escaped slaves found on board. His daughter’s recollection of his funeral is a fitting tribute to his worth. Nothing was “so impressed upon my memory as the sight of the little group of weeping black men and women that gathered around my father’s casket, and in sobbing tones spoke of his goodness to them in the old days of slavery, when he saved them from being sold and separated from kith and kin.”

John Dean (1813-1863, R83 S181) arrived in DC in 1862 to take a position in the Treasury Department. He immediately became involved in a series of fugitive slave cases that, because of the interest of persons on both sides of the slavery issue, were covered extensively by the newspapers. His primary focus was to test the applicability of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Because the law referred only to slaves escaping from one State to another, Dean argued, unsuccessfully, that the law did not apply to the District or the Territories. Over the next year he represented 7 freedom-seekers, 4 of which were ordered returned to their owners. A fifth, Andrew Hall, enlisted in the army and thus escaped recapture. As a result of his work Dean was extremely unpopular among the Maryland slave owners. He began to fear for his life, and an altercation with Hall’s owner resulted in his being charged with assault. Dean contracted and died of pneumonia before the case could be heard in court.

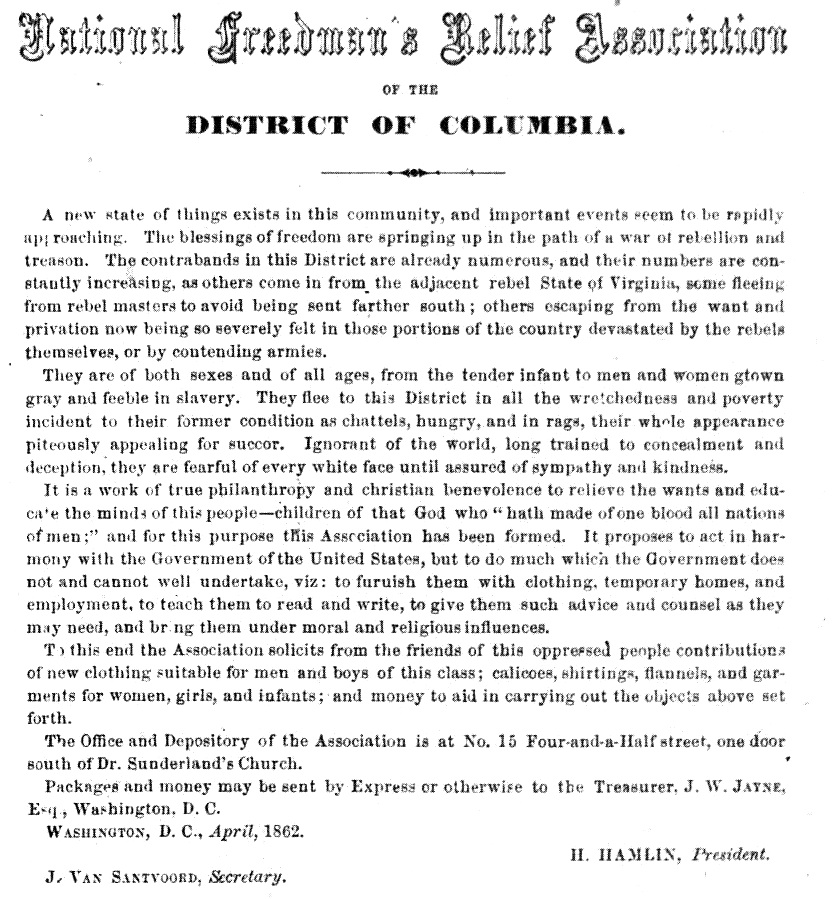

Hannibal Hamlin (1809-1862, R64 S75) was a cousin of Hannibal Hamlin, Lincoln’s first vice president. He arrived in DC in 1861 to accept a position in the Treasury Department. By early April 1862 it was generally believed that President Lincoln would sign the bill to emancipate the slaves living in the District. Already freedom seekers from Virginia and Maryland were arriving in large numbers in the hope of obtaining freedom and seeking work in the military units occupying the city. In late March/early April Hannibal Hamlin served as chairman of a committee to discuss the formation of the National Freedman’s Relief Association (NFRA) of D.C. whose mission was to provide food and clothing to the refugees and prepare them for freedom. The group met on April 9th to formalize the organization and Hamlin was elected their President. He worked tirelessly, soliciting contributions from his Boston and Quaker friends, acquiring provisions and organizing medical services. In the fall he traveled to Fortress Monroe to observe conditions among the contrabands there. Ignoring the advice of family and friends, his health gave out and he died in November 1862.

Congressional is proud to have such men interred on our grounds. We hope you will visit their burial places, and keep their stories alive.